The early hours of Thursday, May 23, 1918, cling to your skin. Your body pushes against the heavy, muggy air as beads of sweat surface on your brow.

The morning, like many others in New Orleans, is uncomfortable, humid, and all-encompassing.

The street you’re walking down is mostly empty, save for a few stragglers. The street lamps make shadows of their figures, but soon, the darkness consumes them.

The clopping of hooves and creaking of carriage wheels disappear into the distance.

Hurrying down Upperline Street, you pass closely stacked shotgun homes, their inhabitants deep in slumber.

Within seconds, you turn onto Magnolia Street and stare into the night. The darkness ahead of you is deep and silent.

A flutter of movement catches the corner of your eye, but you ignore it. These late nights tend to play tricks on the weary.

You continue on your journey, and like the people before you, the darkness consumes you, too.

The Axeman’s Beginnings

If anyone heard the attack on Thursday, May 23, 1918, no one came forth to stop it or raise the alarm.

No one realized anything was amiss until around 4:45 am. Strange groans from an adjacent room woke Andrew Maggio up from a deep, intoxicated sleep.

That night, Andrew, Joseph Maggio, his wife, Catherine, and other family members had been celebrating. Andrew was off to the Navy, a promising prospect for the family.

When Andrew finally went to bed, Joseph and Catherine were still awake, but the festivities had ended hours before, so any noise coming from anywhere in the house was unusual.

Andrew knocked on the wall that divided his and his older brother’s bedrooms and received no response.

The house was quiet beside the groans coming from the next room. After a few minutes of waiting, Andrew ran out of the house in a panic and sprinted down the block to his brother Jacob’s house.

Soon, sunlight would break, and the discovery in Joseph’s room would set the beginning of a nightmare that would grip New Orleans in terror for months.

The Idea of Vendetta

To understand the complexity of this story, you have to understand two things—the shared experiences of Italian immigrants in 19th and 20th-century New Orleans and their general distrust of American authority.

The influx of Italian immigrants began in earnest in the 1880s. The need for cheap labor after the Civil War led to increased immigration. Most of these Italian arrivals were Sicilian.

Sicilians made up over 80 percent of Italian immigrants by the late 19th century. Their arrival continued through the 1890s, and by the century’s turn, New Orleans boasted the largest Italian community in the South.

The relationship between sugar planters and Italian laborers was precarious but mutually beneficial. Sugar planters appreciated the Italians’s hard work and tenacity. In turn, the money Italians earned and carefully saved allowed them to establish a financially comfortable life in the United States.

Most Italians opted for opening fruit stands or grocery stores. By the 1900s, Italians owned groceries all over Louisiana. Despite their financial success, Italians still faced racial prejudice.

Italians’ misunderstanding of American racial beliefs and their willingness to work alongside Black Americans caused many white Americans to distrust them. Tragically, the largest mass lynching of Italians occurred in New Orleans after the assassination of Police Chief David Hennessy.

The distrust was double-sided. Italians didn’t trust American authorities, so they settled conflicts through a custom known as “the vendetta.” Vendettas were violent, and it wasn’t uncommon for disputing parties to get into shooting and knife fights.

The Story of Mrs. Maggio

Although much of the couple’s early life is unknown, the shared experiences of Italian immigrants may help paint a better picture of their lives.

Joseph and Catherine Maggio were Italian grocers. They ran their barroom and grocery store out of the first floor of their home at the corner of Magnolia and Upperline Streets.

The Axeman’s reign of terror began with their murders in 1918. However, some evidence suggests that the Axeman’s operation began as early as 1910 with attacks perpetrated by an assailant nicknamed The Cleaver.

Regardless of whether the killings before 1918 were the Axeman’s doing, the murders between 1918 and 1919 showed an escalation in violence not seen in previous crime scenes.

Joseph and Catherine’s deaths were brutal. The attacker slit their throats and bludgeoned them. The attack was so vicious that specks of blood coated the walls and ceiling of the room.

Catherine died instantly, but Joseph survived until a little after his brothers found him.

Initial suspicion fell on Andrew. How was it possible that he heard nothing during the attack? Why did the attacker spare him?

However, after intense questioning, police released a tearful Andrew. Other evidence led investigators to suspect a different perpetrator.

A disturbing discovery was made a few miles from the crime scene—a note written in chalk. The note read: “Mrs. Maggio is going to sit up tonight, just like Mrs. Tony.”

Mrs. Tony Schiambra had been a victim of the murders committed by The Cleaver between 1911 and 1912. The Maggio attack resembled those previous murders. The Cleaver targeted Italian grocers and entered the properties by chiseling a panel out of the back door. He also killed his victims with an axe.

The Maggios attack resembled Mrs. Schiambra’s. The attacker entered by chiseling a single panel out of the rear exterior of the Maggio’s door. The axe used to murder the couple belonged to them, and the attacker had left it in their bathtub. The attacker also left bloody clothes and a razor in and around the home.

Although some debate exists, the assailant took little or no money. Visible jewelry and money were left untouched. Finally, accounts of an unknown man around the couple’s residence further cemented the investigators’ suspicions.

Could it be the same killer, or was it the work of someone carrying out a vendetta?

All these questions swirled around the investigators’ heads.

The Jekyll and Hyde Concept

A month went by before the next attack. On June 27, 1918, an assailant brutally assaulted Polish grocer Louis Besumer and his partner, Harriet Lowe, with an axe. Similar to the Maggios, Besumer lived in the vicinity of his grocery store. The weapon also belonged to Besumer and was found in the home’s bathtub.

However, key differences existed in the Besumer and Lowe case. The sedated and delirious Lowe pointed the finger at an Afro-Caucasian individual. So police arrested Lewis Oubicon, a Black man recently employed by Besumer. They eventually released Oubicon due to a lack of evidence.

Soon after, Lowe accused Besumer of attacking her. Besumer came under suspicion, and investigators searched his home. There, they found letters written in German, Russian, and Yiddish.

Police began to suspect that Besumer was a German spy and attacked Lowe because she discovered his identity. However, they released him after two days in their custody.

Months after the attack, Lowe, whose condition had further deteriorated, accused Besumer again. Police arrested Besumer, and he spent nine months in prison before his acquittal. Lowe eventually died of her injuries.

Similar to the Maggios murder, the Lowe and Besumer case went cold.

The Next Killing Attempts

Another attack followed on August 4, 1918. A pregnant mother of three, Mary Schneider, was violently beaten with a lamp from her bedside table.

Although initially attributed to the Axeman, the attack did not follow the same pattern as the others. The attacker ransacked Schneider’s home and made off with an axe and over a hundred dollars. Schneider wasn’t Italian, and the attacker didn’t use an axe when he assaulted her.

Schneider survived and delivered a healthy baby. Her case also went cold.

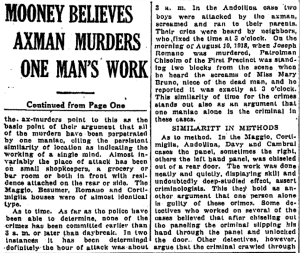

The One-Man Theory

Less than a week after Schneider’s beating, someone attacked Italian barber Joe Romano with an axe. Romano’s nieces, Pauline and Mary Bruno ran to his room after hearing the commotion. They found Romano bleeding out and his attacker running into the night.

The sisters described the assailant as a dark-skinned, heavy-set man wearing a dark suit and slouched hat.

Similar to the other murders, the attacker took little or no money, left a bloody axe at the crime scene, and chiseled away the back door panel to enter the house. Romano was not a grocer, but his family operated a small grocery store from the front of the house he lived in.

Also similar to the Maggio attack, neighbors reported seeing and chasing off attempted intruders from their homes in the previous days.

The Romano murder threw New Orleans into a frenzy. The New Orleans Police Department received nonstop calls with tips and suspicious sightings. Men stood watch over the families armed with guns until sunrise.

Then, all went quiet. The city went without an Axeman attack for seven months.

The nightmare continued on Tuesday, March 11, 1919. Screams from the Cortimiglia home alerted the Gretna neighborhood of a horrible scene.

Neighbor Iorlando Jordano ran to the Cortimiglia’s home and found Rosie Cortimiglia bleeding from severe head wounds and her two-year-old daughter, Mary, hanging from her arms—dead.

Rosie’s husband, Charles, was also assaulted. He and Rosie both survived.

During their hospital stay, Gretna police questioned them about the attack. Both denied knowing or seeing their attacker.

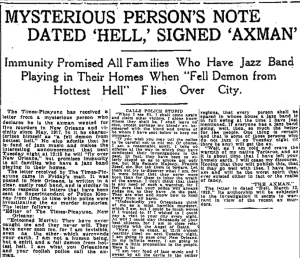

Times-Picayune – March 16, 1919 (NewsBank)

Although the Cortimiglia attack closely resembled the Axeman’s modus operandi, Gretna police persisted with other suspects.

Investigators arrested Rosie as a material witness upon her release from the hospital. After intense interrogation, she blamed the elderly Jordano and his son, Frank.

The police arrested the father and son despite a complete lack of evidence. The Jordanos were tried and convicted.

They were released less than a year later when Rosie retracted her story to the Times-Picayune. She stated that police intimidation led to her accusation of the Jordanos. Without Rosie’s testimony, the case eventually fell apart. It remains unsolved.

The more attacks occurred, the more questions that arose. How was the assailant slipping in and out of homes without detection and with such ease? Why did he always rely on axes found in people’s homes, and what was the motivation behind the brutality?

For some, the sheer savageness of the attacks and the savviness of the perpetrator pointed to a being of supernatural origin. It didn’t help that just days after the Cortimiglia attack, The Times-Picayune received a letter that would confirm people’s fears of an unhuman killer.

The Night of All Jazz

The letter that the Times-Picayune received attested to the Axeman’s reign of terror in New Orleans. The letter read:

Hottest Hell, March 13, 1919

Esteemed Mortal of New Orleans: The Axeman

They have never caught me and they never will. They have never seen me, for I am invisible, even as the ether that surrounds your earth. I am not a human being, but a spirit and a demon from the hottest hell. I am what you Orleanians and your foolish police call the Axeman.

When I see fit, I shall come and claim other victims. I alone know whom they shall be. I shall leave no clue except my bloody axe, besmeared with the blood of he whom I have sent below to keep me company.

If you wish you may tell the police to be careful not to rile me. Of course, I am a reasonable spirit. I take no offense at the way they have conducted their investigations in the past. In fact, they have been so utterly stupid as to not only amuse me, but His Satanic Majesty, Francis Josef, etc. But tell them to beware. Let them not try to discover what I am, for it were better that they were never born than to incur the wrath of the Axeman. I don’t think there is any need of such a warning, for I feel sure the police will always dodge me, as they have in the past. They are wise and know how to keep away from all harm.

Undoubtedly, you Orleanians think of me as a most horrible murderer, which I am, but I could be much worse if I wanted to. If I wished, I could pay a visit to your city every night. At will I could slay thousands of your best citizens (and the worst), for I am in close relationship with the Angel of Death.

Now, to be exact, at 12:15 (earthly time) on next Tuesday night, I am going to pass over New Orleans. In my infinite mercy, I am going to make a little proposition to you people. Here it is:

I am very fond of jazz music, and I swear by all the devils in the nether regions that every person shall be spared in whose home a jazz band is in full swing at the time I have just mentioned. If everyone has a jazz band going, well, then, so much the better for you people. One thing is certain and that is that some of your people who do not jazz it out on that specific Tuesday night (if there be any) will get the axe.

Well, as I am cold and crave the warmth of my native Tartarus, and it is about time I leave your earthly home, I will cease my discourse. Hoping that thou wilt publish this, that it may go well with thee, I have been, am and will be the worst spirit that ever existed either in fact or realm of fancy. – The Axeman.

Times-Picayune – March 16, 1919 (NewsBank)

On Tuesday, March 18, 1919, every dance hall, café, and bar in New Orleans reached capacity. The sound of professional and amateur jazz bands streamed out of nearly every house in the city.

That night, New Orleans went without an Axeman attack.

The letter inspired local jazz composer Joseph John Davilla to write “The Mysterious Axeman’s Jazz (Don’t Scare Me Papa).” The sheet music cover depicts a frenzied and panic-stricken family playing jazz music.

Although the letter sent New Orleans into an all-night jazz, drinking, and dancing frenzy, its authenticity was never proven. Historians argue that the writing in the letter shows a sophistication that the actual Axeman likely didn’t possess. Some even believe Davilla wrote the letter to attract sales for his Axeman-inspired piece.

The Question of Who’s Next

More attacks with similar characteristics to the others followed in close succession.

The Axeman attacked grocer Steve Boca on Sunday, August 10, 1919. On Wednesday, September 3, 1919, an intruder broke into Sarah Laumann’s apartment and beat her with an axe. Both Boca and Laumann survived but couldn’t remember anything from the attack.

The final reported Axeman attack occurred on Monday, October 27, 1919. An intruder entered Mike and Esther Pepitone’s house and repeatedly struck Mike in the head. Esther, sleeping in another room, woke from the noise. She ran to Mike’s room to find a large, axe-wielding man fleeing the scene.

Mike died from his injuries, and like Boca and Laumann, Esther could not identify the attacker.

The Pepitone attack was the last to occur in New Orleans. Although some suspect that the Axeman went on to attack Italian grocers in other parts of the state, no conclusive evidence exists.

The Search Continues

Over a hundred years have passed since the last confirmed Axeman murder, but the legend of the Axeman lives on. The story of his rampage is still shared at slumber parties and around campfires. Amateur sleuths still comb through case files, trying to figure out the Axeman’s identity. You can find all types of podcasts and articles written about him.

It’s important to note the multiple failings that led such a man to continue attacking people with impunity.

- A lack of understanding of Italian culture in New Orleans led to incorrectly suspected vendetta cases.

- Communication breakdowns between police departments resulted in lost time and increased danger.

- Misidentification of the Cleaver and the Axeman by the NOPD.

Finally, you must understand that in the early 20th century, there was no word to describe a serial killer. DNA evidence wasn’t in existence, and the study of psychology was in its infancy.

The legend of the Axeman of New Orleans continues to incite curiosity, but it’s important to remember the faces and facts behind the case.

The Axeman’s attacks were brutal and tormented an entire city. The attacks left people fearful of sleeping where they should have felt the safest—their homes.

Have you heard the story of the New Orleans Axeman before? Let us know in the comments!

Once a Pelican State CU member, always a member—through life’s milestones, we’ll always be there to help you with your financial needs. Your Financial Family for Life. Give us a call at 800-351-4877.